2023

Solo show at Kutlesa Gallery - Gouldal, Switzerland

Exhibiting period: Oct 27 - Dec 2, 2023

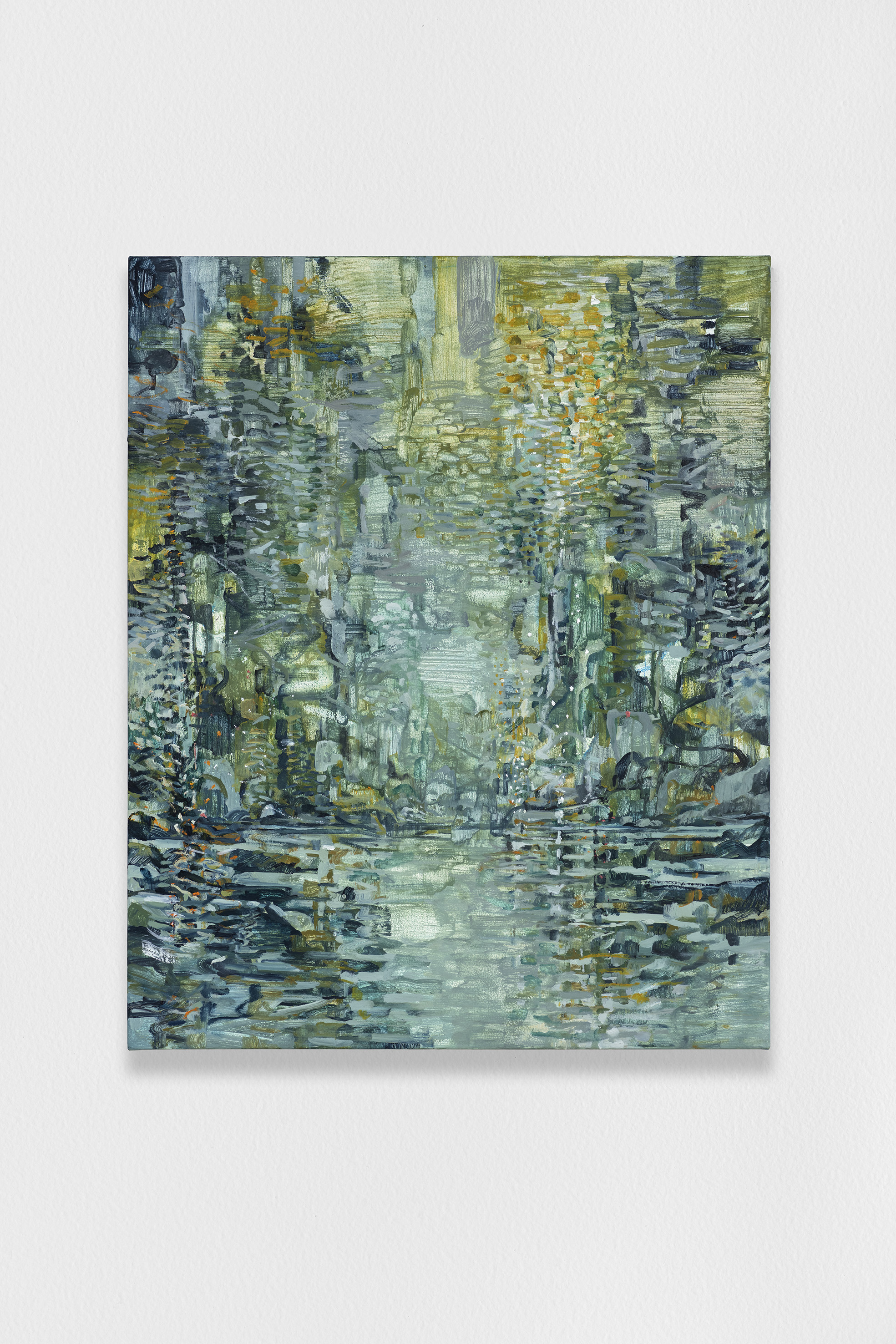

Alexandre Wagner’s paintings share a common thematic catalyst: the creation of a space resembling a landscape. Brush strokes evoke an undulating motion that suggest horizon lines, cliffs, rivers, and forests, rendered in palettes of earth tones and vibrating, electrifying greens and blues. When viewing in series, one after another, the pictorial field develops a rhythm, repeating like a mantra, in which the figurative elements gradually disappear, and the true focus of the paintings emerges: color, movement, and light.

The result is a simple organization of the landscape: an almost abstract, archaic, primitive organization, without defined time and place - a space that, on the other hand, could encompass all times and places, void of any trace of human presence. Engulfed by a mist, a disorientation caused by the non-literality of the spaces, they retain the indefiniteness of a dream.

Reduced to this primary idea, the landscape serves as a motif for paintings that address, above all, issues related to the history of painting itself. Decidedly pictorial, these works materialize into images for a brief moment; upon subsequent viewings, these same images are overshadowed by the painting’s substance: material, technique, application, gesture. The vigorous brushstrokes, which almost sink into the canvas, remove more paint than they deposit on the surface, transforming into a continuous movement of scraping and excavation that contrasts with the delicate layers of highly diluted, almost liquid paint.

At the core of these works is the desire to remain on the threshold between abstraction and figuration, to inhabit an area where doubt is more important than certainty, a tension and experience perhaps only possible due to the paradoxes under which the paintings are constructed.

2022

Solo show at Gate Project - New York, USA

Exhibiting period: Jun 29 - Sep 30, 2022

Text by Tie Jojima

Undoing Landscapes

At first glance, the work of Brazilian artist Alexandre Wagner (b. 1986) presents the viewer with the familiar tropes of landscape paintings: a patch of dense vegetation on the margins of the composition, a riverbed, the rising moon, and an implied horizon. But the repetition of this classic syntax across his works compels us to take a closer look at the details of each piece. As we do so, we are invited to follow the small traces of paint scrupulously, yet precariously, applied to the canvas. The artist then engages with the landscape tradition only to undo its core attributes through the brevity of his gestures, the small scale of his works, and the construction of a space that shifts between indefinability and disorientation.

Landscape painting has a long history in Western art and a specific tradition linked to colonialism in the art of the Americas since the eighteenth century. Reflecting social concerns and epistemological shifts created by advances in technology, landscape is a canonical mode of conceiving of and representing nature, which played a central role in creating imaginaries for eighteenth- and nineteenth-century colonization and nation-building efforts in the Americas. In the twentieth century, ideas associated with landscape have negotiated interpretations of abstract art. In the twenty-first century, landscapes have been linked to our increasing concern with environmental degradation as well as the ubiquity of the digital world and its specific modes of visuality, which challenge our sense of place and space.[1] Alexandre Wagner counters this overdetermined tradition through the tenuousness of his gesture, by undoing representation, and by building layers of affect that may reach us as we read his traces.

Rather than planning his works through preparatory drawings and sketches, a practice common to painters, Wagner begins his paintings on the basis of a personal and emotional response to art history. They emerge from fragments of artworks belonging to a canon that might be called “global” art history: from Chinese ink painting to postimpressionism and early twentieth-century Latin American art. Choosing a small section of these sources as the starting point of his works, the artist slowly departs from the initial reference as his own work emerges. The source works are completely lost in the process as he organizes his paintings according to an inner logic of reflection, opposition, and the mirroring of each brushstroke. Wagner labors at the canvas in a process of doing and undoing, and then looking away and looking back at the work, adjusting it until he gets it right.

While the works selected for this exhibition evoke landscapes, they also invite the viewer to dwell on the surface of the canvas itself. Looking at each work as a whole—and taking it in at a single glance— the viewer might experience it in its totality as a landscape. However, the effect on the viewer shifts significantly as they observe the piece further. The shallow picture plane situates each work between a constructed space and an abstraction, calling attention to the details of the painterly marks applied onto the canvas itself. As we reorient our gazes from the painting as a whole to the details of its brushwork, we perceive numerous gestures, most of them small, repetitive, slow, and somewhat fragmented. For instance, a single brushstroke may be applied with different intensity at its beginning and end or may shift direction just slightly throughout its course, breaking away from its initial path.

Utilizing thin, diluted paint, which he applies layer upon layer to the canvas, the artist creates an effect of transparency. His brushstrokes sometimes result in the removal of paint from the canvas’s surface, allowing colors to emerge in this ambiguous process of addition and subtraction of painterly matter. The scale and orientation of his works are counterintuitive when we consider the logic of the large-scale, almost cinematic vistas that have defined the landscape tradition: Wagner’s works are relatively small and oriented vertically, thus paralleling the body of the viewer who faces them. The artist moves away from the immersive experiences of large-scale abstract works or landscape paintings, as well as the broad gestures that claim visual space while making bold statements about the artist’s self. Wagner instead inscribes his small and somewhat fragmented gestures on the canvas to avoid imposing a specific effect on the viewer, inviting them to explore its myriad details as they project their gaze over the work. From the interstices of a suggested representation and the details of the work emerges a landscape centered on the vulnerability of the artist’s gesture and its capacity to empty out space.

Alexandre Wagner’s work is rich with paradoxes. The thinness of the paint and hesitancy of the brushstrokes allow for transparency and even emptiness, despite his process being carefully considered and involving an accumulation of material. Likewise, his work creates space for personal, intimate encounters—both his encounter with the original piece and the viewer’s encounter with his paintings—while building on a tradition that is so historically dense that this intimacy is easily lost.

---

[1] For a survey of twenty-first-century landscape painting, see Barry Schwabsky, Landscape Painting Now: From Pop Abstraction to New Romanticism (New York: DAP, 2019).

---

Tie Jojima is a associate curator at Americas Society in New York and a PhD Candidate in Art History at the Graduate Center, CUNY, with specialization in modern and contemporary Latin American art. Her larger research interests encompass performance art, technology, and pornography in the 1970s and 1980s, as well as contemporary Asian diasporic art practices in Latin America.

---

2021

Solo show at Galeria Marília Razuk - São Paulo, Brasil

Exhibiting period: May 27 to July 24, 2021

Text by Kiki Mazzucchelli

Água-viva ( jellyfish), Alexandre Wagner’s first exhibition at Galeria Marília Razuk, brings together a set of paintings that, at first, can be perceived as contemporary developments of one of the most recognized genres within the pictorial tradition: the landscape. Even though it is possible to identify a theme in the scenes of dirt roads, skylines and woodlands presented here, this more immediate take would set the work within the key of a certain atavistic romanticism, which, as I see it, takes the focus out of other aspects that seem to be more determining factors in the work.

The way the paint is diluted and applied, the different applications and intensities found in one single pictorial field, the chromatic palette which plays with the contrasts between light and shadow; all of this attests to the importance given by the artist to the actual creation of the painting, putting in the background a bigger commitment to illusionism or representation. In other words, the landscape works as a sort of theme for paintings that, above all, deal with problems related to painting itself. Decidedly pictorial (malerisch), the pieces coalesce in images even if only for an instant. The next moment, the color stands out, the translucency, the different textures: the very matter of a painting.

This constant oscillation is one of the most striking characteristics of Wagner’s work; something that may only be possible due to the scale of this works, which never reaches heroic proportions, limiting themselves to the small and medium-sized format and invariably — and even counter-intuitively — vertical. The disintegration of the image, coupled with the treatment given to a pictorial space of modest dimensions, conveys an idea of fragility to these paintings, situating them outside an historic facet of painting associated with a virtuous and incisive masculinity that does not allow for hesitation or doubt. Even in the different rhythms created by the expressive stroke — which could appear as signs of assertiveness —, a certain delicacy prevails which, at certain moments, reminds us of the vaporous landscapes of Guignard.

A recurring figure in many paintings in this show is the circle, which sometimes appears as the sun, sometimes as a moon on the horizon in works such as Miragem (Mirage, 2019) and Cachalote (Cachalot, 2019); other times as mysterious orange lanterns on the tree trunks of an enlarged landscape in Lanternas (Lanterns, 2019); and, also, on other occasions, as shiny dots placed slightly to the center of the composition, causing a complete destabilization of the pictorial space. Such is the case for Assa-peixe (Cabobanthus polysphaerus, 2019), a painting in tones of orange and green traversed from top to bottom by a section of color compressed by volumes that stretch towards the center from the top of the canvas. The resulting image could be understood as the aerial view of a dirt trail sided by hills, except for the inclusion of a green circle a little below the center of painting (sun/moon), almost forcing us to notice what we see as the horizon, even if it is the horizon of an indefinite landscape.

This vertigo effect of “losing ground” also happens in paintings such as Cambará (2019), which could be the view from above to the center of a crater, a horizon, the reflection of a sun in a lagoon seen from above this same crater. Beyond any type of representation, the circle seems to function in these works as some kind of device that serves to anchor the compositions, in so much as it creates a focal point amidst the layers of watery strokes that suggest a matter in flow, in a movement towards the exterior of the painting. That is, these circles end up creating some kind of center in the midst of a movement of erosion of the image predominant in these paintings.

Much like jellyfish, the set of works presented in this exhibition seems to possess a changing morphology; they are paintings in which the landscape formulates the abyss of space and the abyss of image. They pull away, thus, from a long lineage of Western landscape paintings that distinguishes nature from culture, the latter trying to domesticate or placate the former. Alexandre Wagner’s work, on the contrary, seems to want to incorporate the living and in constant mutation of natural organisms, rejecting narrative in favor of the reality of the painting matter, at the same time without resorting to the spiritual or traditional justifications traditionally associated with the origins of the Western abstract painting. Much like jellyfish, these are invertebrate paintings.

---

Kiki Mazzucchelli is an independent curator and critic. She is a regular contributor at Art Review (London), as well as an occasional contributor to other specialist publications including Art Forum (USA), Art Agenda (USA), Frieze (London), Mousse (Italy) and Terremoto (Mexico). She has curated the 'solo projects' section of Pinta Art Fair (London, 2013/4) and Arco (Madrid, 2015) and has been on the jury for Gasworks artist residencies for Argentinian (Erica Roberts) and Latin American (Shelagh Wakely) artists since 2015. Recent publications include the essay "The São Paulo Biennial and the Rise of Contemporary Brazilian Art" (in Contemporary Art Brazil, ed. Hossein Amirsadegui and Catherine Petitgas, London: Transglobe/ Thames & Hudson, 2012); a chapter on São Paulo's art scene in Art Cities of the Future - 21st Century Avant-Gardes (London: Phaidon, 2013) and a chapter on Brazilian art in Brazil: a celebration of contemporary Brazilian culture (London: Phaidon, 2014).

---

Água-Viva

Água-viva, primeira exposição de Alexandre Wagner na Galeria Marília Razuk, reúne um conjunto de pinturas que, em um primeiro momento, podem ser percebidas como ramificações contemporâneas de um dos gêneros mais reconhecidos dentro da tradição pictórica: a pintura de paisagem. Embora seja possível identificar uma unidade temática nas vistas de estradas de terra, horizontes e matas apresentadas aqui, essa leitura mais imediata situaria o trabalho dentro da chave de um certo romantismo atávico; a qual, em minha opinião, desvia o foco de outros aspectos que me parecem mais determinantes no trabalho.

O modo como a tinta é diluída e aplicada, as diferentes faturas e intensidades encontradas em um mesmo campo pictórico, a paleta cromática que joga com os contrastes entre luz e sombra; tudo isso atesta à importância dada pelo artista aquilo que diz respeito ao fazer da pintura, colocando em segundo plano um compromisso maior com o ilusionismo ou a representação. Em outras palavras, a paisagem funciona como uma espécie de mote para pinturas que, acima de tudo, tratam de problemas relativos à própria pintura. Decididamente pictóricos (malerisch), esses trabalhos coalescem em imagens como que por um breve instante; no momento seguinte, sobressai a cor, a translucidez, as diferentes texturas: a própria matéria da pintura.

Essa oscilação constante é uma das características mais marcantes da obra de Wagner; algo que talvez seja possível apenas devido a escala desses trabalhos, que nunca atinge proporções heroicas, limitando-se ao pequeno e ao médio formato e invariavelmente - e até mesmo contra-intuitivamente - verticais. O esfacelamento da imagem, aliado ao tratamento dado a um espaço pictórico de dimensões modestas, confere uma ideia de fragilidade à essas pinturas, situando-as fora de uma vertente histórica da pintura associada a uma masculinidade virtuosa e incisiva que não permite hesitação ou dúvida. Até mesmo nos diferentes ritmos criados pela pincelada expressiva - que poderiam aparecer como índices de assertividade-, prevalece uma certa delicadeza que, em alguns momentos, lembra a graciosidade das paisagens vaporosas de Guignard.

Uma figura recorrente em muitas das pinturas que integram a exposição é o círculo, que aparece ora como um sol ora como uma lua no horizonte em trabalhos como Miragem (2019) e Cachalote (2019); outras vezes como misteriosas lanternas alaranjadas nos troncos de uma paisagem alagada em Lanternas (2019); e, ainda, em outros momentos, como pontos luminosos levemente deslocados do centro da composição que acarretam uma completa desestabilização do espaço pictórico. Esse é o caso de Assa-peixe (2019), uma pintura em tons de laranja e verde atravessada de cima à baixo por uma área de cor comprimida por volumes que se estendem em direção ao centro desde os vértices da tela. A imagem produzida poderia ser entendida como a vista aérea de um caminho terra ladeado por morros, exceto pela inclusão de um círculo verde colocado um pouco abaixo do centro da pintura (sol / lua), que quase nos força a perceber o que vemos como um horizonte, ainda que horizonte de uma paisagem indefinida.

Esse efeito vertiginoso da “perda do chão” acontece também em pinturas como Cambará (2019), que poderia ser a vista de um céu desde o centro de uma cratera, um horizonte, o reflexo de um sol em uma lagoa observado de cima dessa mesma cratera. Para além de qualquer tipo de representação, a figura do círculo parece funcionar nesses trabalhos como uma espécie de dispositivo que serve para ancorar as composições, na medida em que cria um ponto focal em meio às camadas de pinceladas aquosas que sugerem uma matéria em fluxo, num movimento que vai em direção ao exterior do quadro. Ou seja, esses círculos acabam por criar uma espécie de centro em meio ao movimento de erosão da imagem que predomina nessas pinturas.

Como as águas vivas, o conjunto de obras apresentadas nessa exposição parece possuir uma morfologia cambiante; são pinturas em que a paisagem engendra o abismo do espaço e o abismo da imagem. Afastam-se, assim, de uma longa linhagem da pintura de paisagem ocidental que distingue a natureza da cultura, buscando domesticar ou apaziguar a primeira. O trabalho de Alexandre Wagner, pelo contrário, parece querer incorporar o aspecto vivo e em constante mutação dos organismos naturais, rejeitando conteúdos narrativos em favor da realidade da matéria da pintura, ao mesmo tempo sem recorrer às justificativas espirituais ou racionais tradicionalmente associadas às origens da pintura abstrata no ocidente. Como as águas-vivas, são pinturas invertebradas.

---

Kiki Mazzucchelli is an independent curator and critic. She is a regular contributor at Art Review (London), as well as an occasional contributor to other specialist publications including Art Forum (USA), Art Agenda (USA), Frieze (London), Mousse (Italy) and Terremoto (Mexico). She has curated the 'solo projects' section of Pinta Art Fair (London, 2013/4) and Arco (Madrid, 2015) and has been on the jury for Gasworks artist residencies for Argentinian (Erica Roberts) and Latin American (Shelagh Wakely) artists since 2015. Recent publications include the essay "The São Paulo Biennial and the Rise of Contemporary Brazilian Art" (in Contemporary Art Brazil, ed. Hossein Amirsadegui and Catherine Petitgas, London: Transglobe/ Thames & Hudson, 2012); a chapter on São Paulo's art scene in Art Cities of the Future - 21st Century Avant-Gardes (London: Phaidon, 2013) and a chapter on Brazilian art in Brazil: a celebration of contemporary Brazilian culture (London: Phaidon, 2014).

---

2018

Solo show at Galeria Bolsa de Arte - São Paulo, Brazil

Text by Ana Estaregui

---

In Alexandre Wagner's work, there is a sound that is almost a whisper. His paintings are permeated by this subtle wind that gently lifts the fabrics of the flags, tilts poles and masts, and makes the waters and treetops sway slowly.

His landscapes have a low light that harks back to another time—past or future, one cannot tell—or perhaps, they are another dimension of these same spaces, as if the paintings were the memory of these places or dreams yet uninhabited. Some of them resemble the lunar surface or another planet. Opaque, they carry a repeated weight, a unique slowness, another gravity.

In this series of works, Alexandre highlights the solitary night in landscapes that evoke deserts and abandoned places where there is no human presence, only scarce and already deteriorated traces: a tent, a mast, a flag, an old house, a tire. These artifacts, the sole inhabitants of these spaces, seem to survive preserved in an extended time, as in a slow dream where a pair of trees can also be a ghost.

In the case of landscapes that could be daytime, the brightness seems to be from the moment before the day has dawned, when the sky is already lightening but the sun's rays have not yet appeared. It's as if the paintings seek the limit of the night, as if they stretch it to see how far it continues to be night: yellow, white, greenish. In Alexandre's paintings, there is no high noon sun, evident. And when it appears in the sky, it blends with the moon. If, in Drummond's poem, objects turn into night, in Alexandre Wagner's paintings, the night unfolds into layers, depths, and eventually turns into day.

---

Existe no trabalho de Alexandre Wagner um som que é quase um rumor. Suas pinturas são permeadas por esse vento sutil que ergue de leve os tecidos das bandeiras, que inclina estacas e mastros, que faz as águas e as copas das árvores tremularem devagar.

Suas paisagens têm uma luz baixa que remete a uma outra época – passada ou futura, não se sabe – ou talvez sejam uma outra dimensão desses mesmos espaços, como se as pinturas fossem a lembrança desses lugares ou sonhos ainda inabitados. Algumas delas se parecem com a superfície lunar ou de outro planeta. Opacas, há nelas um peso que se repete, uma vagarosidade própria, uma outra gravidade.

Nesta série de trabalhos, Alexandre evidencia a noite solitária em paisagens que remetem a desertos e lugares abandonados onde não há presença humana, mas seus indícios escassos e já deteriorados: uma barraca, um mastro, uma bandeira, uma casa velha, um pneu. Esses artefatos, únicos habitantes desses espaços, parecem sobreviver conservados em um tempo estendido, como num sonho lento onde um par de árvores também pode ser um fantasma.

No caso das paisagens que poderiam ser diurnas, a luminosidade parece a do momento em que o dia ainda não nasceu, de quando o céu já está clareando, quando ainda não há raios de sol. É como se as pinturas buscassem o limite da noite, como se a esticassem pra ver até onde continuam sendo noite: amarelas, brancas, esverdeadas. Nas pinturas de Alexandre não há sol a pino, evidente. E quando aparece no céu, ele se confunde com a lua. Se no poema de Drummond os objetos se convertem em noite, nas pinturas de Alexandre Wagner a noite se desdobra em camadas, profundidades e, eventualmente, se converte em dia.