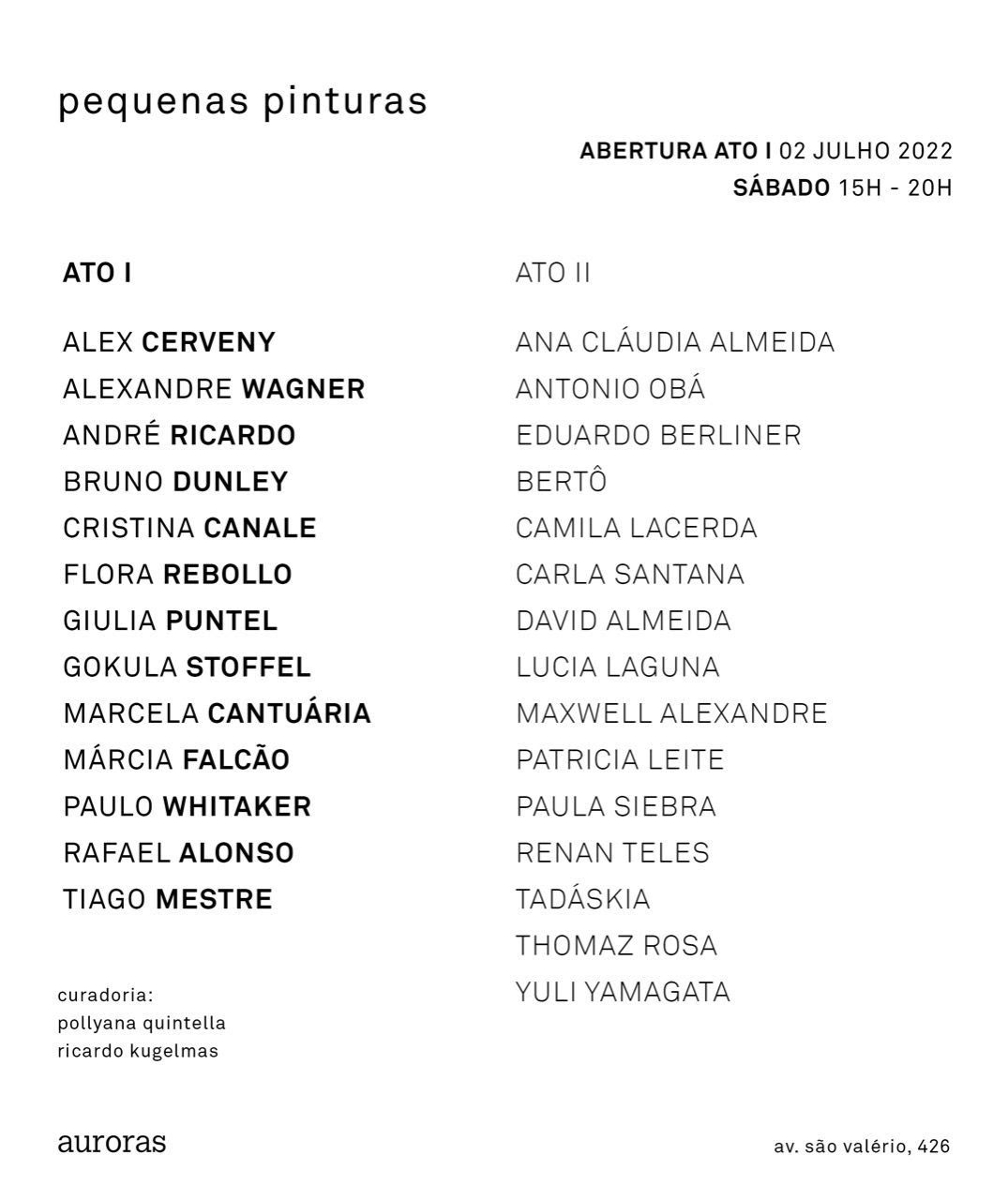

Group show at Auroras - São Paulo, Brasil

Exhibiting period: July 27 - Aug 13, 2022

Fagulha

2022

Solo show at Gate Project - New York, USA

Exhibiting period: Jun 29 - Sep 30, 2022

Text by Tie Jojima

Undoing Landscapes

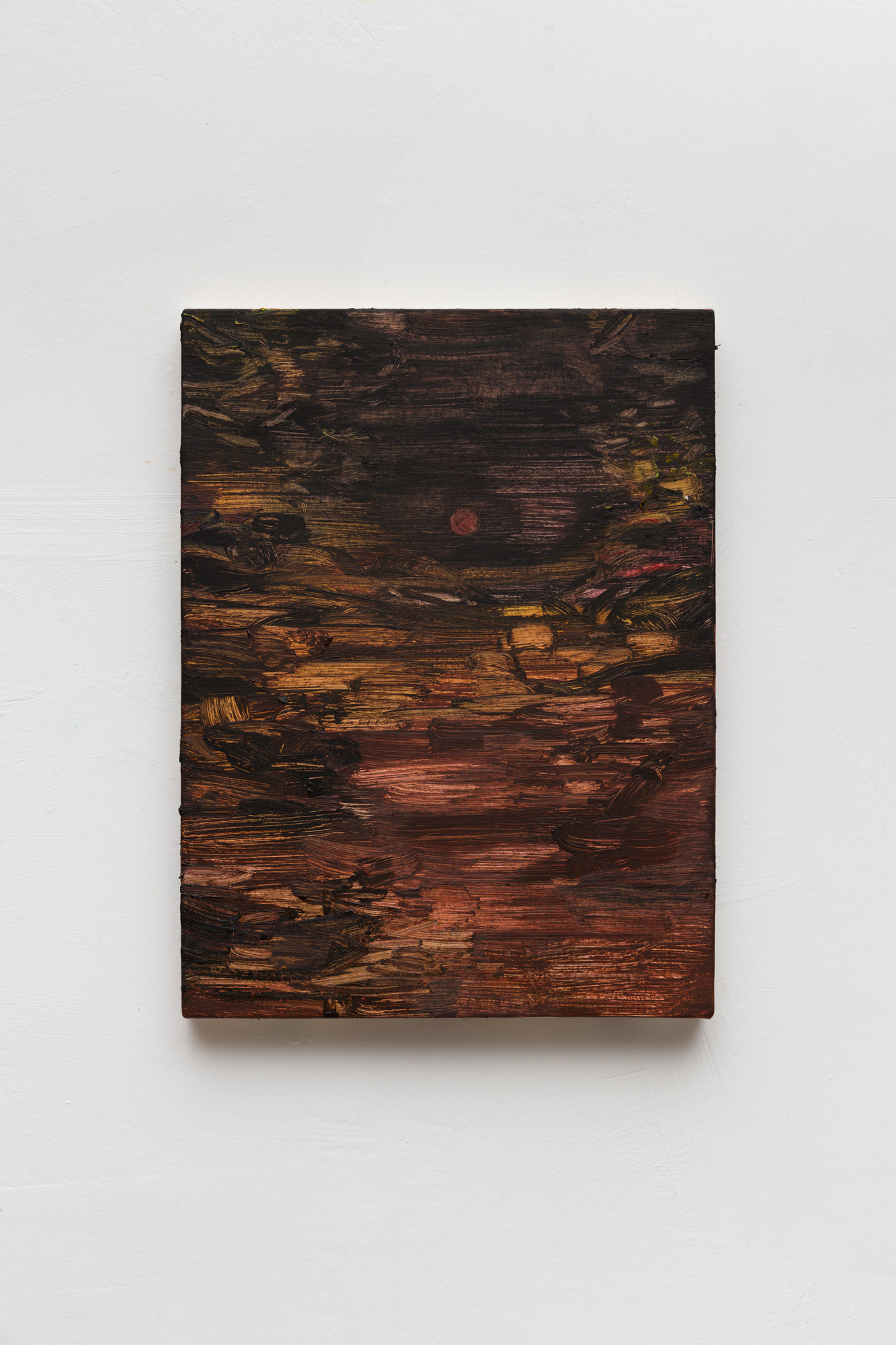

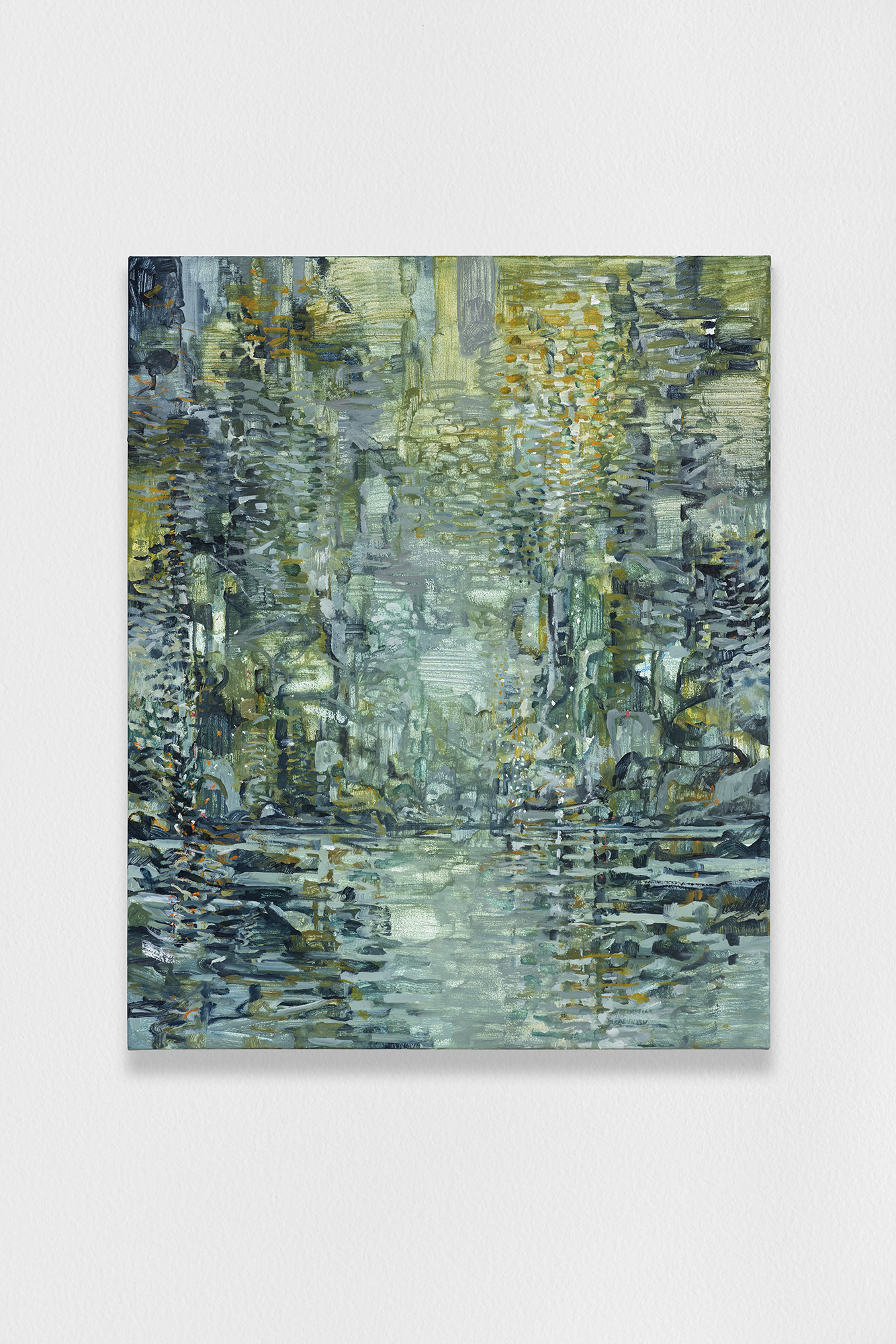

At first glance, the work of Brazilian artist Alexandre Wagner (b. 1986) presents the viewer with the familiar tropes of landscape paintings: a patch of dense vegetation on the margins of the composition, a riverbed, the rising moon, and an implied horizon. But the repetition of this classic syntax across his works compels us to take a closer look at the details of each piece. As we do so, we are invited to follow the small traces of paint scrupulously, yet precariously, applied to the canvas. The artist then engages with the landscape tradition only to undo its core attributes through the brevity of his gestures, the small scale of his works, and the construction of a space that shifts between indefinability and disorientation.

Landscape painting has a long history in Western art and a specific tradition linked to colonialism in the art of the Americas since the eighteenth century. Reflecting social concerns and epistemological shifts created by advances in technology, landscape is a canonical mode of conceiving of and representing nature, which played a central role in creating imaginaries for eighteenth- and nineteenth-century colonization and nation-building efforts in the Americas. In the twentieth century, ideas associated with landscape have negotiated interpretations of abstract art. In the twenty-first century, landscapes have been linked to our increasing concern with environmental degradation as well as the ubiquity of the digital world and its specific modes of visuality, which challenge our sense of place and space.[1] Alexandre Wagner counters this overdetermined tradition through the tenuousness of his gesture, by undoing representation, and by building layers of affect that may reach us as we read his traces.

Rather than planning his works through preparatory drawings and sketches, a practice common to painters, Wagner begins his paintings on the basis of a personal and emotional response to art history. They emerge from fragments of artworks belonging to a canon that might be called “global” art history: from Chinese ink painting to postimpressionism and early twentieth-century Latin American art. Choosing a small section of these sources as the starting point of his works, the artist slowly departs from the initial reference as his own work emerges. The source works are completely lost in the process as he organizes his paintings according to an inner logic of reflection, opposition, and the mirroring of each brushstroke. Wagner labors at the canvas in a process of doing and undoing, and then looking away and looking back at the work, adjusting it until he gets it right.

While the works selected for this exhibition evoke landscapes, they also invite the viewer to dwell on the surface of the canvas itself. Looking at each work as a whole—and taking it in at a single glance— the viewer might experience it in its totality as a landscape. However, the effect on the viewer shifts significantly as they observe the piece further. The shallow picture plane situates each work between a constructed space and an abstraction, calling attention to the details of the painterly marks applied onto the canvas itself. As we reorient our gazes from the painting as a whole to the details of its brushwork, we perceive numerous gestures, most of them small, repetitive, slow, and somewhat fragmented. For instance, a single brushstroke may be applied with different intensity at its beginning and end or may shift direction just slightly throughout its course, breaking away from its initial path.

Utilizing thin, diluted paint, which he applies layer upon layer to the canvas, the artist creates an effect of transparency. His brushstrokes sometimes result in the removal of paint from the canvas’s surface, allowing colors to emerge in this ambiguous process of addition and subtraction of painterly matter. The scale and orientation of his works are counterintuitive when we consider the logic of the large-scale, almost cinematic vistas that have defined the landscape tradition: Wagner’s works are relatively small and oriented vertically, thus paralleling the body of the viewer who faces them. The artist moves away from the immersive experiences of large-scale abstract works or landscape paintings, as well as the broad gestures that claim visual space while making bold statements about the artist’s self. Wagner instead inscribes his small and somewhat fragmented gestures on the canvas to avoid imposing a specific effect on the viewer, inviting them to explore its myriad details as they project their gaze over the work. From the interstices of a suggested representation and the details of the work emerges a landscape centered on the vulnerability of the artist’s gesture and its capacity to empty out space.

Alexandre Wagner’s work is rich with paradoxes. The thinness of the paint and hesitancy of the brushstrokes allow for transparency and even emptiness, despite his process being carefully considered and involving an accumulation of material. Likewise, his work creates space for personal, intimate encounters—both his encounter with the original piece and the viewer’s encounter with his paintings—while building on a tradition that is so historically dense that this intimacy is easily lost.

---

[1] For a survey of twenty-first-century landscape painting, see Barry Schwabsky, Landscape Painting Now: From Pop Abstraction to New Romanticism (New York: DAP, 2019).

---

Tie Jojima is a associate curator at Americas Society in New York and a PhD Candidate in Art History at the Graduate Center, CUNY, with specialization in modern and contemporary Latin American art. Her larger research interests encompass performance art, technology, and pornography in the 1970s and 1980s, as well as contemporary Asian diasporic art practices in Latin America.

---